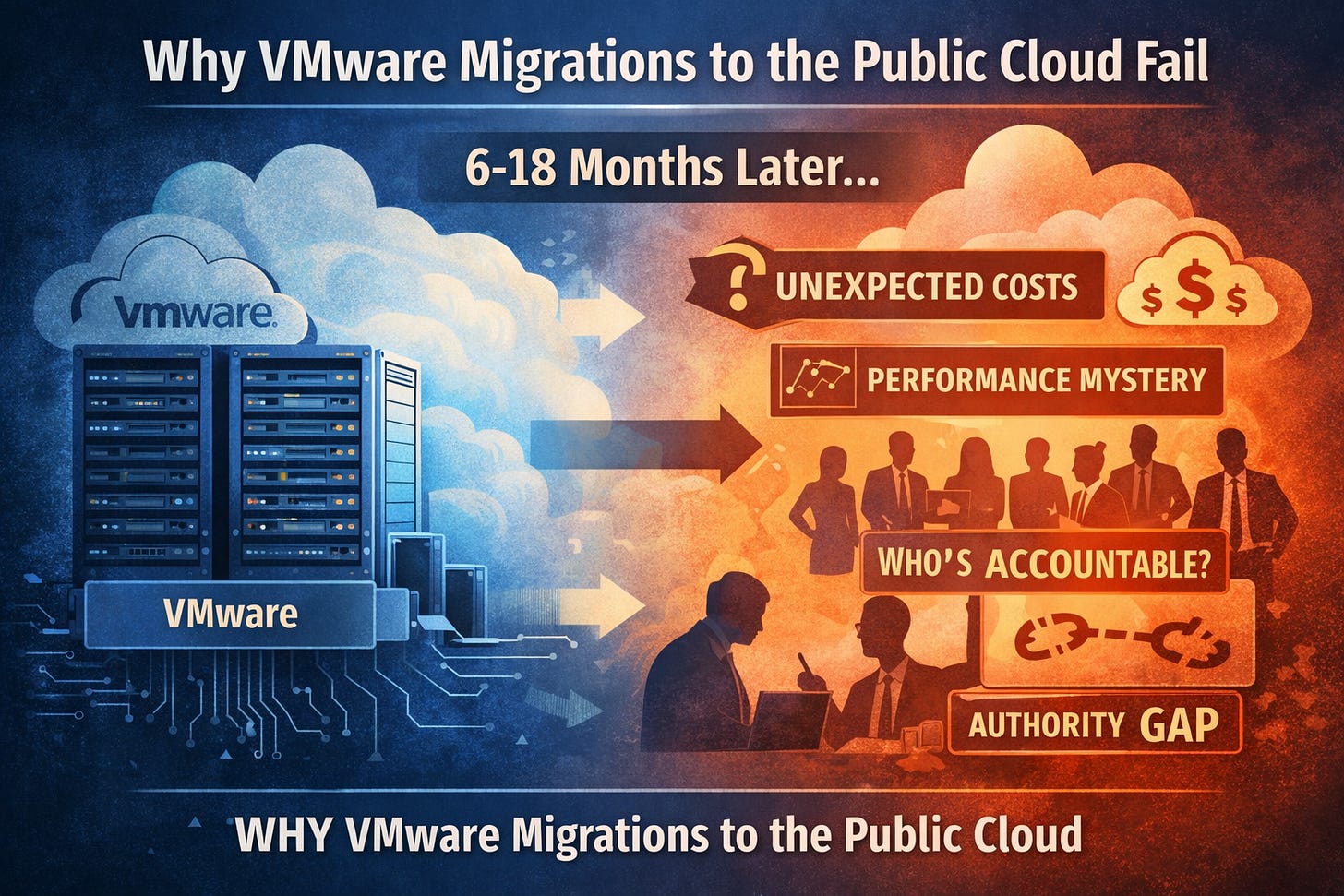

Why VMware Migrations to the Public Cloud Fail

Most VMware-to-cloud migrations don’t fail on day one.

They fail six to eighteen months later.

The workloads are up.

The applications run.

The dashboards are green.

And yet, something feels off.

Costs are unpredictable.

Incidents are harder to explain.

Performance tuning turns into guesswork.

Platform teams are blamed for decisions they didn’t make.

This isn’t because VMware is “better” than the cloud.

It’s because VMware was doing work you didn’t realize you’d need to replace.

VMware Didn’t Just Run Your Workloads

VMware wasn’t just virtualization software.

It was an operating model.

Over time, VMware encoded thousands of small decisions on your behalf:

where workloads lived

how contention was resolved

which failures were tolerated

how recovery priorities were enforced

how much risk was acceptable during disruption

Those decisions weren’t documented as “judgment.”

They were embedded in defaults, policies, and platform behavior.

And they worked — especially under stress.

What Changes During a Lift-and-Shift

When enterprises lift VMware workloads into a public cloud, they usually focus on:

compatibility

performance parity

network connectivity

security controls

What they rarely focus on is this:

Who is now allowed to make the decisions VMware used to make?

In the cloud:

placement decisions are abstracted

scaling behavior is probabilistic

contention is resolved by the provider

cost becomes a runtime outcome, not a design input

You didn’t just move execution.

You inherited a new decision authority model.

And in most cases, no one explicitly accepted responsibility for it.

The Failure Doesn’t Show Up Immediately

Early on, things feel easier:

fewer tickets

faster provisioning

less visible friction

That’s because the cloud platform is making decisions for you.

But when something goes wrong — a cost spike, a performance incident, a regional failure — the questions change:

Who decided this workload could scale this way?

Who approved this cost tradeoff?

Who owns the recovery behavior now?

Who can explain why the system behaved like this?

And that’s where migrations start to fail.

The Real Failure Mode: Authority Evaporation

VMware encoded judgment.

The cloud provides execution.

During migration:

VMware’s decision authority disappears

Cloud authority is inherited implicitly

Accountability remains organizational

No one explicitly placed authority.

No one anchored accountability.

So when leadership asks for answers, authority starts moving:

governance tightens controls

platform teams centralize decisions

product teams lose autonomy

velocity drops

shadow systems appear

This back-and-forth isn’t political.

It’s structural.

Why “Better Cloud Architecture” Doesn’t Fix This

Most remediation efforts focus on:

better tagging

stricter budgets

more guardrails

tighter reviews

Those help at the margins.

They don’t address the core problem:

You replaced a platform that made decisions with one that assumes you’ll decide — but never said who.

Until decision authority is explicit, every fix is temporary.

The Question Enterprises Skip

The most important VMware migration question isn’t:

“How do we move the workloads?”

It’s:

“Where does decision authority live after VMware is gone?”

If that answer is unclear, the migration hasn’t failed yet —

it’s just waiting for its first real test.

A Model That Explains This Pattern

I’ve written a longer piece on The CTO Advisor that formalizes this failure mode — and others like it — into a general model called the Decision Authority Placement Model (DAPM) - Pronounced Dap-eem

It explains:

why VMware exits feel harder than expected

why cloud migrations destabilize over time

why governance crackdowns follow incidents

and why enterprises oscillate after failures

You can read the full paper here:

👉 DAPM Post

Why This Matters for Cloud Teams

If you’re on a platform or cloud team, this pattern matters because:

you’ll inherit blame for decisions you didn’t authorize

you’ll be asked to “fix” behavior you don’t control

and you’ll be reorganized after incidents you couldn’t prevent

Naming the problem doesn’t solve it by itself.

But it does let you have the right conversation before the migration “fails” in all the ways that don’t show up in a status report.